🌟 Recap Before We Start

In Lesson 5, we explored mapping and visibility.

Remember how stove knobs are easier when their placement matches the burners, or how a highlighted tab tells you which page you’re on?

That was about making controls match real results and making system states visible.

Today, we move deeper. We will discover why sometimes, even if mapping is good, people still feel lost.

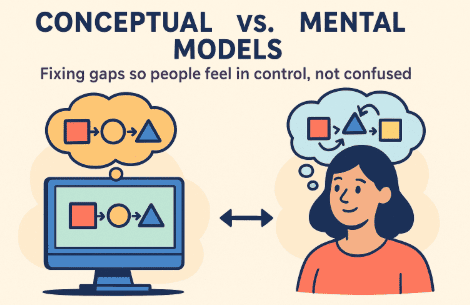

The key reason is a gap between two “models”: the conceptual model (designer’s blueprint) and the mental model (user’s belief).

1. What Are “Models,” Anyway?

A model is just a simplified picture of how something works. It doesn’t have to be the full truth, but it helps you predict outcomes.

Imagine you’re six years old and pressing a light switch.

Your mental model might be: “Switch up = light on. Switch down = light off.” That’s enough to use it. But in reality, the conceptual model is much more complicated: wires, currents, a circuit breaker, and a bulb filament glowing because electrons move.

So, two different pictures exist:

-

Conceptual Model (Designer’s Model): The real structure and process behind the system.

-

Mental Model (User’s Model): What the person thinks is happening when they interact with it.

2. Why Mental Models Matter

Humans rarely know how things actually work. Instead, we survive by using good-enough guesses.

For example:

-

You don’t know the chemistry of soap, but your mental model says “soap removes dirt.”

-

You don’t know how Wi-Fi transmits signals, but your mental model says “when Wi-Fi bars are full, internet is strong.”

These mental models let you act quickly without technical knowledge.

Now here’s the design problem: if the user’s mental model doesn’t match the designer’s conceptual model, confusion and errors happen.

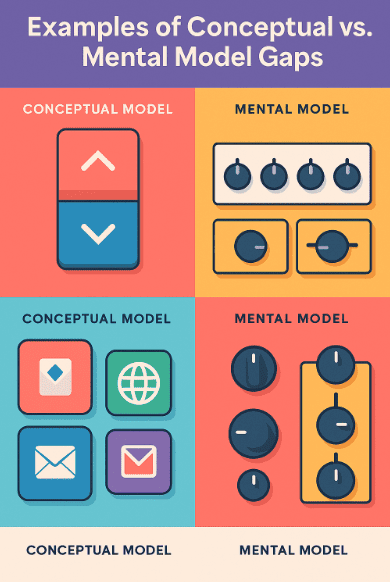

3. Examples of Conceptual vs. Mental Model Gaps

Example 1: The Floppy Disk Save Icon

-

Mental Model: “This little square = Save.”

-

Conceptual Model: There is no floppy disk anymore. Data is written to solid-state drives in blocks of memory.

-

Gap: People click the floppy even though they may never have seen one in real life.

Example 2: The Trash Bin for Deletion

-

Mental Model: “Dragging to the bin destroys the file.”

-

Conceptual Model: The operating system only moves it to a temporary folder (Recycle Bin), until space is overwritten.

-

Gap: Many people panic thinking the file is gone forever when it’s not.

Example 3: Elevator Door Close Button

-

Mental Model: “Pressing the button makes the door close faster.”

-

Conceptual Model: In many modern elevators, the button is disabled or just signals maintenance systems.

-

Gap: Users feel they control it, but often they don’t.

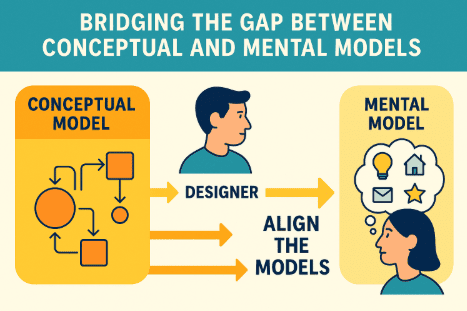

4. Bridging the Gap: Why Designers Must Care

Designers cannot expect users to learn the full conceptual model. It’s too complex. Instead, designers must create interfaces that align with mental models or gently guide users to form better ones.

Think of it like building a bridge between two islands:

-

One island is the designer’s technical reality.

-

The other is the user’s belief and habit.

-

The interface is the bridge that connects them.

5. Principles for Closing the Gap

-

Match User’s Language

Use familiar terms (“Save,” “Print,” “Send”) instead of technical jargon like “Commit changes to persistent storage.” -

Make Models Visible

Progress bars show that “something is happening.” Without them, the user’s mental model might think the system is frozen. -

Offer Gentle Correction

Example: If someone types “htp://” instead of “http://,” the browser corrects it silently or suggests a fix. -

Teach Through Feedback

Undo, redo, and previews help users gradually refine their mental models without punishment.

5. Principles for Closing the Gap

-

Match User’s Language

Use familiar terms (“Save,” “Print,” “Send”) instead of technical jargon like “Commit changes to persistent storage.” -

Make Models Visible

Progress bars show that “something is happening.” Without them, the user’s mental model might think the system is frozen. -

Offer Gentle Correction

Example: If someone types “htp://” instead of “http://,” the browser corrects it silently or suggests a fix. -

Teach Through Feedback

Undo, redo, and previews help users gradually refine their mental models without punishment.

6. Story: Grandma and the Computer

My grandma once clicked the “X” at the top corner of Word. She panicked when the text disappeared. Her mental model: “I deleted my document.”

The conceptual model: the file was still saved on disk, only the program window was closed.

A better design would have matched her mental model by showing:

“Your document is safe. Closing just hides it. You can reopen it from Recent Files.”

That little message could build a stronger bridge between models.

7. Advanced View: Norman’s “Gulf of Execution and Evaluation”

Don Norman, one of the fathers of Human-Computer Interaction, described two gulfs:

-

Gulf of Execution: The gap between what the user wants and the actions available.

-

Gulf of Evaluation: The gap between the system’s feedback and the user’s understanding.

Bridging these gulfs means aligning conceptual and mental models tightly.

8. Why This Matters for Intuitive Design

An interface feels “intuitive” not because it’s magical, but because the mental model users already have matches the design’s conceptual model.

That’s why swiping on a smartphone feels obvious—because it maps to real-world mental models of moving paper or turning pages.

🌟 Key Takeaways

-

A conceptual model is how the system is really designed.

-

A mental model is how the user thinks it works.

-

Gaps between them cause confusion, errors, or mistrust.

-

Designers’ job: build bridges using familiar language, good feedback, and gentle guidance.